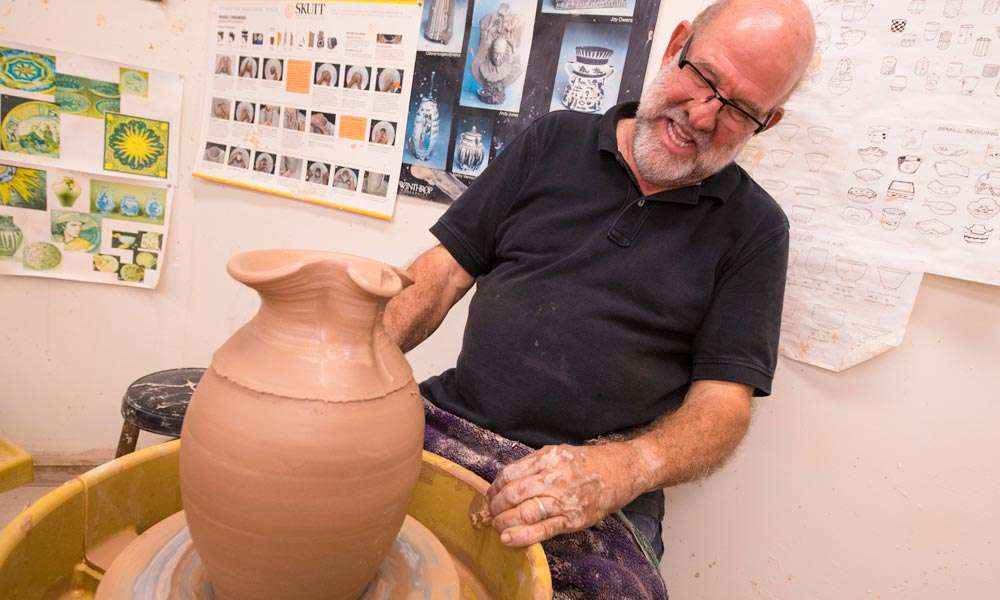

When Michael Galletta made his way from Orlando back to Sanford, Fla., for his 50th grade-school reunion, he realized that, at an early age, he’d been pigeonholed. It wasn’t as the altar-boy at his Catholic church. It wasn’t as the boy with an Italian name whose family ran a neighborhood grocery. “I was the kid who was designated as the artist,” says Galletta. “I was always drawing.” But Galletta, the art professor and program director for ceramics, sculpture and drawing on Valencia College’s East Campus, also refused to be pigeonholed too young. The serene sheen of a newly opened sketchbook wasn’t what attracted him in the long run—not really. “I played with everything that was three-dimensional,” he says. “I was always digging clay out of the stream near our house. I was much more fascinated with Play-Doh than with drawing.” That little nugget of Galletta’s history wouldn’t surprise anyone who has seen the variety of his work in ceramics, scattered throughout the filled-to-bursting pottery studio at Valencia and also through his Winter Park home. A simple coffee mug flares out at the bottom and is marked inside and out by the heavy swirls made by his fingers in the clay. A platter is divided by colors swirling in one direction and slashing in another. A clay sculpture in the garden at Crealdé School of Art shows a beating heart covered by the flora and fauna of the southern bayou. “I don’t feel I have a particular style,” he says. “It’s very eclectic. I don’t like to get stuck in one thing.” He finds his ideas not just in pots, but in shapes and surfaces everywhere, and he credits Picasso with the idea that genius can be found in “that obscurity of sources—the way you can put your sources together.” Those ideas wind up in pages and pages of sketchbooks, which Galletta uses as source material months and years later. “By drawing a lot, you can make so many more pieces in your head than you can in your studio,” he says. “You can cram more lifetimes into your lifetime.” Galletta started out studying to be a graphic designer—all those stained-glass windows and intriguing symbols at his Sanford church—but, after watching fellow students on the pottery wheel, switched to ceramics. “It looked like fun,” he says. He studied at Florida Technological University (now UCF) with Stephen Jepson, a well-known pioneer of Central Florida’s pottery community and, after getting a master’s of fine arts at Wichita State University in Kansas, returned home to work at Jepson’s Geneva studio. “He gave me a space, and I bartered with my time. So I made a lot of pots for the studio, and I made my own pots.” Like most potters trying to support themselves by turning out a lot of work, Galletta learned at Jepson’s to work quickly. And, looking around, he eventually found there was something else he’d rather do than production pottery. After filling in for a friend who was on sabbatical from Santa Fe Community College in Gainesville, Galletta discovered that he liked to teach. “I went out to Valencia, and I found that the pottery shop was being used for storage. The kilns didn’t work—well, they really did work, but they were filled with dirt daubers. This was in 1986. I needed a studio to work in, so they offered me the studio and managing the shop.” He worked at Valencia as an adjunct professor and also spent two years teaching at UCF, where he met his wife, Betsy Gwinn (now executive director of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park). Galletta then returned to teach at Valencia fulltime. “Teaching keeps you thinking,” he says. “It’s constantly renewing. Every 14 weeks you have a new group of minds to work with.” Along with ceramics, Galletta teaches drawing and sculpture, often to first-year students who “I want to get them looking at things,” he says. “In a drawing class, because I don’t think of myself as a two-dimensional artist, teaching keeps challenging me on how to represent a three-dimensional world in a two-dimensional reality—and in a way that’s fun. You try to think ‘What am I really doing?’ instead of giving them the standard line.” At 63, Galletta says he has “flirted with” the notion of retirement. But, for a man who surrounds himself with sketchbooks and paper templates for making pots, giving up art isn’t going to happen. “I always have something here I can work on,” he says, gesturing around his living room to the drawings and cut-outs that eventually will transform themselves into tactile works of clay. “I don’t think I’ll retire from being an artist—ever.”

By drawing a lot, you can make so many more pieces in your head than you can in your studio.”

may not be planning to major in art.

The Secret Life of

Valencia’s Master Potter

Valencia’s Master Potter