//BY Linda Shrieves Beaty

Illustrations by Brian Nut

In the quaint downtown of Winter Garden, where yuppies and hipsters and retirees gather, cyclists pedal by and shoppers meander along Plant Street.

But if they were to look up, they might spot the future of urban agriculture—and some Valencia students learning about it.

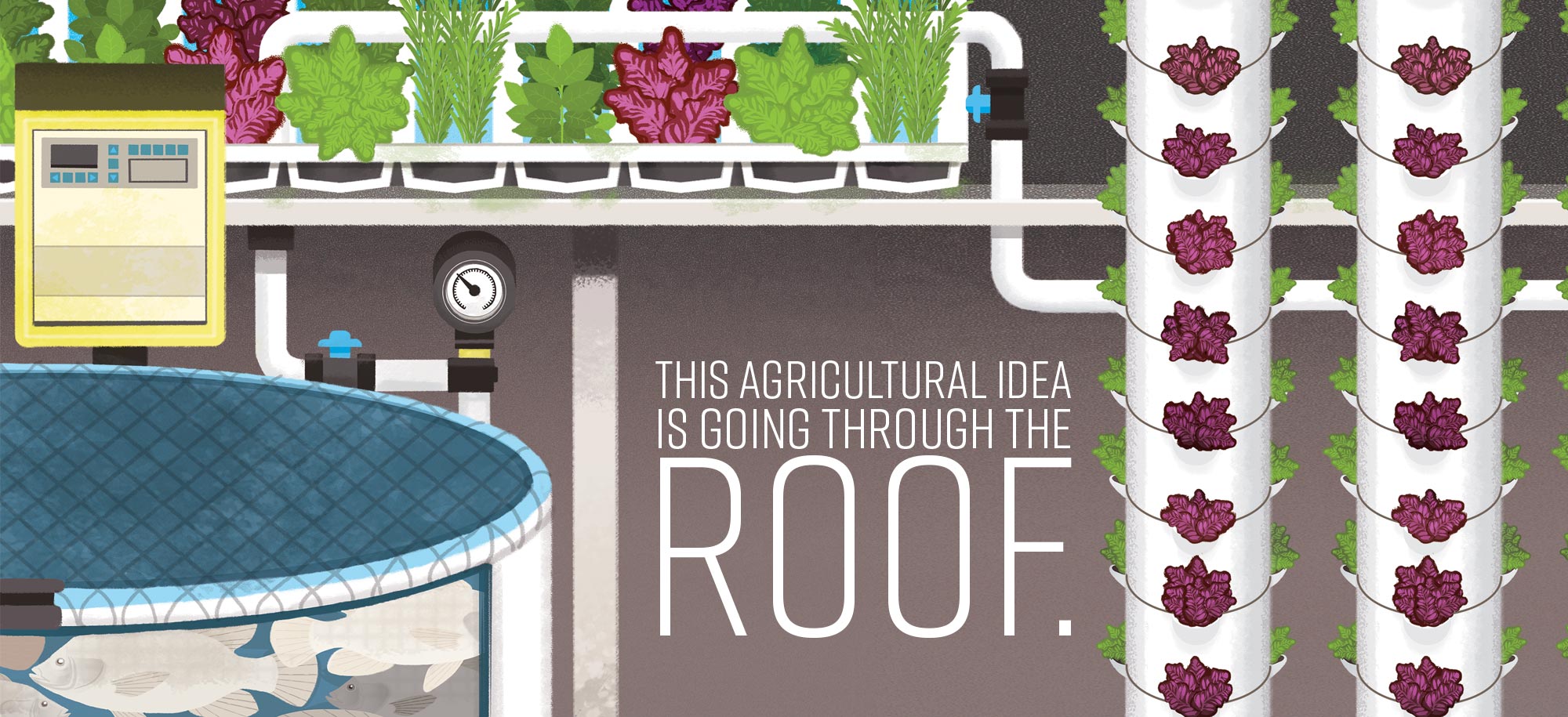

Winter Garden, which bills itself as “a charming little city with a juicy past,” is experiencing a renaissance as it becomes the hip new suburb in Central Florida. And while most of the action takes place on Plant Street, a few stories up is a garden oasis—a rooftop hydroponic and aquaponics garden, which is now part of Valencia’s growing Plant Science and Agricultural Technology Program.

The 3,000-square-foot garden features 1,500-gallon tanks brimming with three different types of fish, above which hang hydroponic gardens filled with varieties of lettuce and herbs. Above the garden, retractable walls and ceilings enable the team to filter sunlight and protect the plants from wind and cold temperatures.

The unique facility was a pet project of Winter Garden citrus grower Bert Roper, who created the rooftop garden in 2009. Roper, who held a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and a master’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh, was also an inventor—and he envisioned the rooftop garden as a demonstration project, to show Floridians and ag students that this could be the future of urban agriculture as land costs rise and water grows scarce.

After Roper’s death in 2012, the garden was operated by Aquatic Ecosystems and then by Pentair, both companies in the hydroponics/aquaponics business. Both companies used the facility as a demonstration greenhouse. But when they expanded their other facilities, they decided to stop operating the rooftop facility in Winter Garden.

So when the Roper family offered Valencia College the chance to take over the lease, Dr. Javier Garces leaped at the chance. Garces, who runs Valencia’s plant science program, has been taking students to Roper’s garden since he started working at Valencia in 2009. “Every semester, I take a class on a field trip there,” says Garces. “I’ve had (Valencia) alumni working there, running the greenhouse.”

Valencia student Kelly Edwards checks basil plants for signs of pests or disease.

The possibilities for Valencia students to use the garden are endless, he says. And students are already lining up for the chance to take classes there—even though the facility is 10 miles from West Campus, where they take their other plant science classes.

“It’s been fascinating,” says Garces. “Students get up there and their jaws drop. They want to know, ‘How can I spend time here? How can I get trained in this type of production?’ I had concerns about it being off campus. But the reaction has been the opposite. I’ve had to tell students to wait another semester to take the classes.”

Garces and Jose Sikaffy, a recent Valencia plant science grad who was hired to serve as the aquaponics greenhouse manager, took over operations at the facility in August 2016. With the assistance of Sikaffy and Tucker Kirkpatrick, another Valencia plant science graduate who was hired to help run the facility, Garces plans to spend the first year of the three-year lease using the garden to teach students in existing courses.

It’s been fascinating. Students get up there and their jaws drop. They want to know, ‘How can I spend time here? How can I get trained in this type of production?’”

“For example, a course in greenhouse operations and management could meet there weekly as a lab session. A class on fertilizers could meet there once a semester to learn about and practice using hydroponic fertilizers. And an entomology class could go there regularly and look for “insect pests,” says Garces.

But the plans go far beyond those basics. Over the next three years, Garces plans to teach students about hydroponics, aquaculture (fish farming), and aquaponics, which blends fish-farming and hydroponics by recycling the water from fish farming to hydroponically grown plants. In the coming years, students will be able to earn technical certificates in those areas—and the college will add a specialization in sustainable agriculture.

Because of the changes, Valencia has changed the name of its agriculture program and now students will earn A.S. degrees in plant science and agricultural technology.

But what’s more exciting will be the variety of plants they’re growing—and the many possibilities for partnerships.

For instance, Chef Ryan Freelove, who in October opened his Market to Table Restaurant on the first floor of the Roper Building, has asked Garces and his students to grow basil, parsley, rosemary, gourmet lettuce, tomatoes, bell peppers, hot peppers and eggplant.

Basil, says Sikaffy, is “a crop that’s expensive to buy and hard to grow.” In the hydroponic towers, Sikaffy plans to grow strawberries and edible flowers.

Meanwhile, lettuce grows in channels—which look remarkably like roof gutters—that hang above the fish tanks. Throughout the season, Sikaffy and Valencia students will harvest 200 heads of lettuce each week.

In addition, Garces and his students will experiment with some unusual crops—including purple cabbage, Chinese green cabbage, yellow and purple cauliflower. “Those are unique crops that you can’t find at the supermarket, but produce that a chef might want,” Garces says.

The fish tanks are currently full of koi, tilapia and hybrid striped bass, a hybrid developed to survive in a southern climate in warmer water. But Garces doesn’t plan to sell the fish; because Valencia doesn’t have a permit to clean and gut the fish on the premises, the fish must be sold whole. And he hasn’t quite figured out who would want to buy whole, rather than filleted, fish. “Honestly, what restaurant wants their kitchen staff busy cleaning and filleting fish?” says Garces.

There’s a huge interest from students and the public in urban agriculture—whether it’s dirt farming or more high-tech farming, like this rooftop hydroponics.”

For now, he is donating the farmed fish to charities—including the Salvation Army and the Central Care Mission—and to Valencia’s culinary program, where culinary students can learn to clean and fillet the fish. In September, Garces donated 120 pounds of hybrid striped bass to chefs Pierre Pilloud and Ken Bourgoin, who used it teach their students how to clean and cook the fish.

It was a great learning opportunity, says Bourgoin. “The students who helped gut and scale the fish had a great opportunity because normally we don’t buy that much fish for a class,” says Bourgoin. “Teams of two in two classes were able to filet the fish off the bone.” They then learned to saute the fish in a Meunière sauce (butter and lemon), and served it with a beurre blanc (browned butter sauce) or a mousseline sauce, which is a hollandaise with whipped cream.

But the primary benefit of the fish is, frankly, their waste—which is used to fertilize the plants. The water in the fish tank, which contains ammonia, nitrites, nitrates, phosphorus, potassium and other micronutrients, is continuously pumped into a grow bed where the plants are located. The plants remove the nutrients from this water, and the clean water is then sent back into the fish tank.

“The fish provide fertilizer for the plants—but they also provide an additional source of potential revenue for us,” says Garces.

Valencia student Keith Grant leans over a fish tank to check on new plantings of red and green lettuce.

Balancing the nutrient levels to keep both plants and fish happy is tricky, says Sikaffy. “The fish like a higher pH; plants like a lower pH. We meet in the middle,” he says. That’s one reason that the previous aquaponics greenhouse operators chose to grow tilapia and koi. “They’re very forgiving,” says Sikaffy.

In the future, however, Garces may explore raising different types of fish—including baitfish, which could be sold whole to fishermen, or he may experiment with fish that live in brackish water, such as redfish or snook. The challenge with growing fish that prefer salty water, though, is finding plants that also can thrive in salty water. “We’re trying to think outside the box,” he says.

Thinking outside the box has become standard procedure for Garces. Already having built a huge cooperative garden with the Edgewood Children’s Ranch, Garces is now trying to figure out how to make the most of this rooftop garden, so that many students can benefit.

In addition to the agriculture students, he envisions teams of business students selling Valencia produce at the weekly farmer’s market in Winter Garden. And he would love to hold a regular farmer’s market on West Campus, so students and faculty could buy fresh produce. Any money raised, he says, “would help keep the facility running and raise funds for the program.”

In addition to raising money, business students “could take on the whole farmer’s market thing and help us keep track of the numbers,” says Garces. “That would be a great experience.”

Valencia student Michael Masucci nets a hybrid striped bass being raised in the tanks of the rooftop garden.

As for Valencia’s agriculture students, they’re excited about the operation—so much so that the classes scheduled to use the rooftop garden are filling up quickly.

“There’s a huge interest from students and the public in urban agriculture—whether it’s dirt farming or more high-tech farming, like this rooftop hydroponics,” says Garces. And for consumers and foodies, there’s growing demand for locally grown produce. “Farmers markets are packed every weekend,” he adds, and restaurants are clamoring for locally grown goods, as the farm-to-table movement continues to grow.

For students looking for a career in agriculture, Garces notes that this type of training opens up new opportunities. “Nationwide and throughout the world, there are big operations that need individuals who have this type of training,” he says. “There’s a couple of operations here in Florida—and a huge hydroponic facility that opened recently in Milwaukee in an old, abandoned brewery.”

Meanwhile, there are also jobs with companies such as Pentair—the company that once operated the greenhouse—which has clients in Saudi Arabia and around the world.

“This is part of the future of agriculture,” says Garces. “This is not the silver bullet, but I do feel strongly that this is a part—and a big important part—of the future of agriculture.”